Historical Overview

Brief Overview:

- Suicide, as a concept, was viewed differently across ancient cultures, sometimes with acceptance and even honor in certain contexts, unlike the predominantly negative view in Judeo-Christian tradition.

- Ancient philosophical perspectives on suicide varied widely, with some Stoics seeing it as a rational choice under extreme duress, while others, like the Pythagoreans and Platonists, generally condemned it.

- Jewish tradition, rooted in the sanctity of life, strongly opposed suicide, associating it with rebellion against God’s sovereignty over life and death.

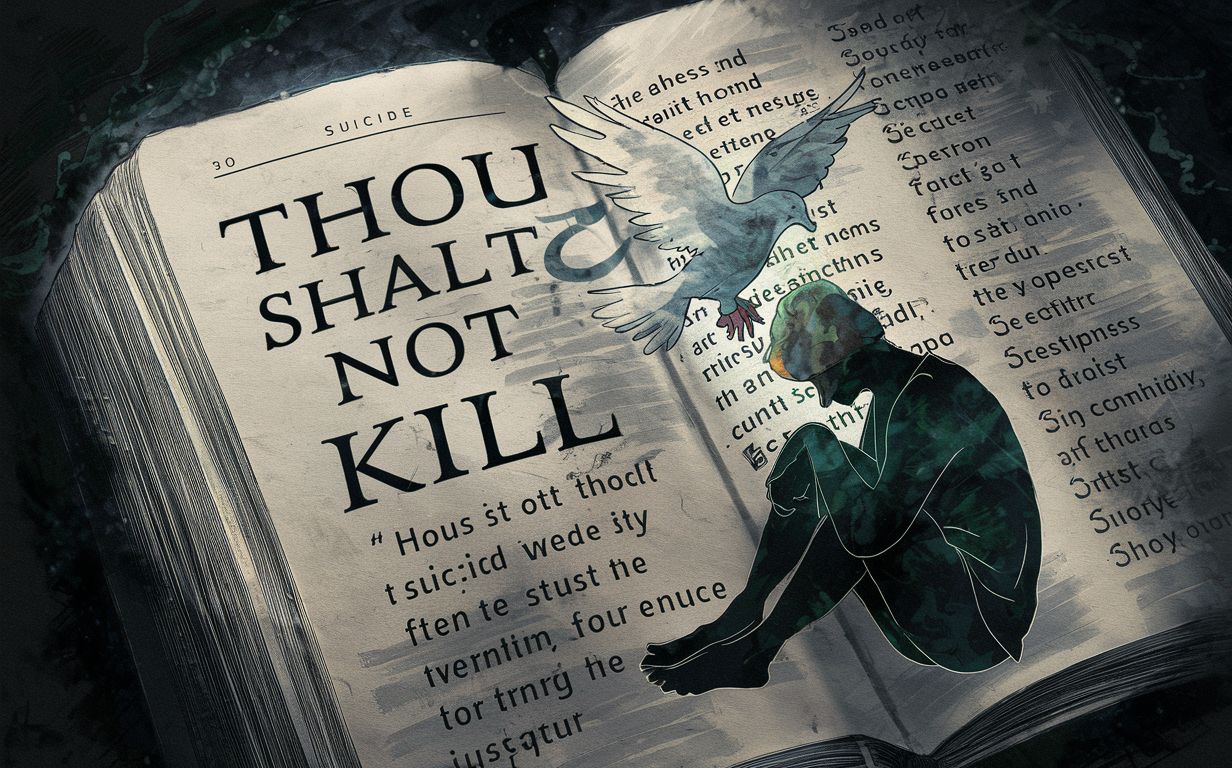

- Early Christian thought inherited and reinforced this Jewish prohibition, viewing suicide as a grave sin against the Fifth Commandment (“You shall not kill”).

- The concept of martyrdom differed significantly from suicide; martyrdom was understood as a passive acceptance of death for faith, not an active seeking of it.

- The historical context of the biblical narratives provides insight into the cultural understanding of life, death, and the afterlife, influencing the interpretation of suicide-related passages.

Detailed Response:

The ancient world lacked a unified perspective on suicide. Cultures such as the Romans and Greeks sometimes saw suicide as an honorable escape from unbearable suffering or dishonor. This is reflected in the stories of figures like Lucretia, who took her own life after being raped, or Cato the Younger, who committed suicide rather than submit to Julius Caesar. However, these instances were often contextualized within specific societal norms and expectations regarding honor and shame.

Jewish law, in contrast, firmly rooted in the belief that God is the author and giver of life, developed a strong prohibition against self-killing. The Old Testament does not contain an explicit commandment against suicide, but the inherent value of life, created in God’s image (Genesis 1:27), is a foundational principle. The preservation of life is a recurring theme, and deliberate self-destruction was understood as a violation of God’s covenant and a rejection of his gifts.

The absence of an explicit, named condemnation of suicide does not denote acceptance. The overwhelmingly life-affirming message of Scripture and tradition demonstrates the Jewish understanding. Life is sacred, and only God has ultimate authority over it. Any usurpation of that authority would be considered gravely wrong.

Early Christian writers continued this, elaborating on the theological and moral objections to suicide. Augustine of Hippo, in his influential work “The City of God,” argued that suicide violates the commandment “You shall not kill” (Exodus 20:13; Deuteronomy 5:17) and is a rejection of God’s gift of life. He further argued that suicide precludes the possibility of repentance, thus jeopardizing one’s eternal salvation.

The distinction between suicide and martyrdom is crucial. Martyrs, like those described in the Book of Maccabees, did not actively seek death but accepted it as a consequence of remaining faithful to God. Their deaths were seen as a witness to their faith, a testament to their belief in the resurrection and eternal life, and a participation in Christ’s own suffering. Suicide, conversely, was understood as a desperate act of self-destruction, a denial of hope and a rejection of God’s grace.

The historical context clarifies that the biblical silence on suicide, in explicit terms, is not an endorsement. Instead, the consistent emphasis on the sanctity of life, both in Jewish and Christian tradition, provides a strong implicit condemnation. The cultural understanding of suicide as a tragic and morally problematic act is deeply embedded within the biblical worldview.

Scriptural Overview

Brief Overview:

- The Bible does not have a verse that states “thou shall not commit suicide.”

- The Bible presents several accounts of individuals taking their own lives, including Saul, Ahithophel, Zimri, and Judas Iscariot.

- These narratives do not explicitly endorse or condemn the act of suicide itself but rather present the circumstances and consequences of their actions.

- The overarching biblical emphasis on the sanctity of life, created in God’s image (Genesis 1:27), implicitly condemns suicide as a violation of God’s sovereignty.

- The Fifth Commandment, “You shall not kill” (Exodus 20:13; Deuteronomy 5:17), is broadly interpreted to include self-killing, as it prohibits the unlawful taking of human life.

- The Bible emphasizes God’s love, mercy, and the possibility of redemption, even in the face of despair, offering a counter-narrative to the hopelessness that often leads to suicide.

Detailed Response:

The Old Testament recounts several instances of suicide, without explicit moral judgment attached to the act itself. King Saul, facing defeat and capture by the Philistines, fell on his own sword (1 Samuel 31:4). Ahithophel, whose counsel was rejected by Absalom, hanged himself (2 Samuel 17:23). Zimri, after his short-lived coup, set fire to the king’s house and died in the flames (1 Kings 16:18). These accounts are presented as factual descriptions of events, focusing on the context and consequences of their actions rather than explicitly condemning the suicide itself.

The lack of direct condemnation in these Old Testament narratives should not be interpreted as approval. The narratives themselves often depict these individuals as acting out of despair, defeat, or a sense of hopelessness. Their suicides are presented as the tragic culmination of their flawed choices and circumstances, not as models to be emulated. The broader context of Scripture, with its emphasis on God’s sovereignty over life and death, implicitly frames these acts as violations of God’s will.

The New Testament account of Judas Iscariot’s suicide (Matthew 27:5) is similarly presented without explicit moral judgment. Judas, overcome with remorse after betraying Jesus, hanged himself. The focus of the narrative is on the consequences of Judas’s betrayal and the tragic nature of his despair, rather than on the act of suicide as a separate moral issue. The narrative highlights the profound sense of guilt and hopelessness that led Judas to this act, serving as a cautionary tale about the destructive power of sin and despair.

The Fifth Commandment, “You shall not kill,” (Exodus 20:13; Deuteronomy 5:17) is central to the biblical understanding of the sanctity of life. While the commandment primarily addresses the unlawful killing of another person, the consistent teaching of the Church has interpreted it to include self-killing. CCC 2280 states, “Everyone is responsible for his life before God who has given it to him. It is God who remains the sovereign Master of life. We are obliged to accept life gratefully and preserve it for his honor and the salvation of our souls. We are stewards, not owners, of the life God has entrusted to us. It is not ours to dispose of.”

The biblical emphasis on God’s love, mercy, and the possibility of redemption provides a powerful counter-narrative to the despair that often underlies suicidal thoughts. The Psalms, for example, are filled with expressions of profound anguish and despair, yet they also consistently affirm God’s faithfulness and offer hope for deliverance. The prophets repeatedly call people to repentance and offer the promise of God’s forgiveness and restoration, even in the face of seemingly insurmountable challenges. “For I know the plans I have for you, declares the LORD, plans for welfare and not for evil, to give you a future and a hope.” (Jeremiah 29:11).

The Bible, while not explicitly condemning suicide with a specific verse, presents a consistent message that affirms the sanctity of human life and God’s sovereignty over it. The narratives of individuals who took their own lives serve as cautionary tales, highlighting the tragic consequences of despair and the importance of seeking God’s help in times of trouble. The overarching message is one of hope, redemption, and the enduring love of God, even in the darkest of circumstances.

Church Overview

Brief Overview:

- The Catholic Church unequivocally condemns suicide as a grave sin, a violation of the Fifth Commandment and a rejection of God’s gift of life.

- The Church teaches that we are stewards, not owners, of our lives, and that only God has the right to determine the time of our death.

- While traditionally those who died by suicide were denied Christian burial, the Church now recognizes the potential for diminished culpability due to psychological factors.

- The Church offers prayers and support for those who have died by suicide and their families, emphasizing God’s mercy and the hope of eternal life.

- The Church actively promotes mental health awareness and suicide prevention, recognizing the importance of addressing the underlying causes of suicidal ideation.

- The Church’s teaching on suicide is rooted in both Scripture and Tradition, reflecting a consistent emphasis on the sanctity of human life from its earliest beginnings.

Detailed Response:

The Catholic Church’s teaching on suicide is rooted in the fundamental principle of the sanctity of human life. God is the author of life, and each human being is created in his image and likeness (Genesis 1:27). This inherent dignity demands respect for life from conception to natural death. Suicide, therefore, is seen as a grave offense against God, oneself, and the community. CCC 2281 states: “Suicide contradicts the natural inclination of the human being to preserve and perpetuate his life. It is gravely contrary to the just love of self. It likewise offends love of neighbor because it unjustly breaks the ties of solidarity with family, nation, and other human societies to which we continue to have obligations. Suicide is contrary to love for the living God.”

The Church’s traditional stance on suicide was very strict. For centuries, those who died by suicide were denied Christian burial, reflecting the belief that suicide was a mortal sin that, without the possibility of repentance, jeopardized one’s salvation. However, the Church’s understanding of mental illness and its impact on human culpability has evolved. While still considering suicide objectively grave, the Church now acknowledges that psychological factors can diminish a person’s responsibility for their actions.

CCC 2282 addresses this nuance: “Grave psychological disturbances, anguish, or grave fear of hardship, suffering, or torture can diminish the responsibility of the one committing suicide.” This recognition reflects a more compassionate and nuanced approach, acknowledging the complex interplay of factors that can contribute to suicidal ideation and actions. It does not condone suicide but recognizes that the person’s freedom and, therefore, their culpability, may be significantly impaired.

The Church, while upholding the objective gravity of suicide, emphasizes God’s infinite mercy and the hope of salvation even for those who have taken their own lives. CCC 2283 states, “We should not despair of the eternal salvation of persons who have taken their own lives. By ways known to him alone, God can provide the opportunity for salutary repentance. The Church prays for persons who have taken their own lives.” This statement highlights the Church’s pastoral concern for those who have died by suicide and their families, offering prayers and support while acknowledging that God’s judgment is ultimately beyond human comprehension.

The Church is actively involved in promoting mental health awareness and suicide prevention. Recognizing that suicidal ideation often stems from underlying mental health issues, the Church encourages individuals to seek professional help and support. Catholic charities and organizations often provide counseling services and resources for those struggling with mental illness and suicidal thoughts. The Church’s pro-life stance extends to advocating for policies and programs that support mental well-being and prevent suicide.

The Church’s position regarding the denial of Christian burials has also seen pastoral softening. While, traditionally, such a burial was denied, Canon Law now allows for it unless it would cause public scandal. The Order of Christian Funerals includes prayers specifically for those who have died by suicide, recognizing the grief and pain of the surviving family members and offering them consolation and hope. The emphasis is on entrusting the deceased to God’s mercy and praying for their eternal rest, while also providing support and healing for those who mourn. The shift is not a change in doctrine regarding the objective gravity of the action of suicide, but a pastoral recognition of the complex circumstances that can surround it and the enduring need for prayer and compassion.